Historical Write-Ups

Below is a compilation of written and reported oral histories provided throughout the years. The below documentation is not a complete history, nor have items been edited or redacted, except for privacy purposes. We appreciate your patience as we continue to add to our collection. If you have any images, newspaper articles, etc. that you would like us to consider adding, please submit them to merrimacshoresca@gmail.com for review.

Merrimac Shores

Merrimac Shores is a part of a 100-acre tract of land first patented by Elizabeth Hawthorne on September 20, 1624. When the area was developed in 1945, it was owned by the Armstrong family. The Armstrong Land and Improvement Company then developed the area, and the covenants were approved and certified on March 25, 1946.

This residential section was named in honor of the Confederate Ironclad Merrimac which engaged the Federal fleet of wooden ships on March 8, 1862 and the next day fought a battle with the Monitor.

The streets were named for the ships involved, their officers and designers. The commander of the Merrimac was Commodore Franklin Buchanan, and the commander of the Monitor was Lt. John Lorimer Worden.

The first house was built in 1946 by Mr. & Mrs. William Gracey at 4014 Buchanan Drive. The second house was built in 1947 by Mr. & Mrs. Robert S. Chandler at 4105 Chesapeake Avenue. The first house in Merrimac Shores-extended was built in 1959 at 3801 Chesapeake Avenue.

Notes of Interest:

- The Indian village "Kicotan" was located here.

- The first trading post "Kicotain" was located nearby.

- A small battle of the War of 1812 was fought here with Major Stapleton Crutchfield and a small band of infantry against the British.

- Blackbeard's Point is nearby.

- It is the former site of a dairy farm.

- It is also the former site of a horse farm and race track.

- In 1940, Joseph B. & Alvin W. Brittingham, Sr., started excavation work which was concluded in 1945. Most of the work was done at the end of Chesapeake Avenue, next to Church Creek and Sussex Apartments. They found many artifacts, such as jugs, pins, fish hooks, tomahawks, arrows and spear heads. These artifacts are on display in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.

by Luther L. Alexander, June 15, 1994

Porter Avenue

The opening of the splendid Monitor Center has pulled me out of my year long writing slump to continue the history of our street names.

There were two Porters involved with the first iron clads with David D. Porter of the Union Navy Department charged with inspecting the completed Monitor and he pronounced it " a perfect success and capable of defeating anything that floated." But I believe Porter Ave. was named after John L. Porter, a naval 'constructor' at the Norfolk Naval Yard (Gosport) working for the Federals until they vacated the yard in 1861. He promptly joined the confederacy. He had thought about ironclads for years and when he was called to Richmond to comment on John Brooke's design, he took a model of one he had made. Most of his design features were adopted on 6/23/1861, and Porter recommended that the burned and sunken USS Merrimack be raised and provide the platform and propulsion for the new CSS Virginia. Porter was tasked with the rebuild and was given $110,000. As usual the cost was more ~ $ 172,000.

John Brooke was the liaison between Porter and Secretary of the Navy, Stephen Mallory in Richmond and Brooke's Type A personality led to open hostility with Porter.

Brooke would inspect the progress and recommend changes to Mallory, who imposed them on a resentful Porter, putting him behind on the schedule. I doubt that the namer of our streets knew about this hostility or they wouldn't have put them together.

Most of the workers doubted that she would float and they stayed onshore when she was launched from the dry dock. Porter was vindicated and a celebration followed. But defects soon became evident, such as the exposed upper wooden hull that was supposed to be 12 inches lower. Hundreds of tons of pig iron were added as well as coal and supplies which brought her deeper. Also, she leaked, had poor ventilation and none of the crew wanted to stay on board at night. But Porter and Brooke were pleased. The CSS Virginia was 262 feet overall with a 178 foot casemate of sturdy oak framing with two layers of two inch iron plates. It sloped at a 36 degree angle to deflect shells, the result of intensive testing on shore. On the bow was a 1500 pound ram.

News of the launch quickly reached the North and work on 'Ericcson's folly' or 'floating hat' were redoubled.

They met on 3/9/1862 after the Virginia had destroyed the Cumberland and Congress the day before. The Monitor successfully protected the grounded USS Minnesota, but was mauled by the Virginia, who returned to Norfolk with the ebbing tide. Both sides claimed victory, of course, but lesson learned was that the era of wooden ships was over.

The press coverage was exuberant giving the most credit to John Brooke and Stephen Mallory. Porter was very upset and began a newspaper campaign to claim his share, but as newspapers do there was no resolution. They had moved on.

Wild ideas of sailing up the East coast to besiege New York were quickly put down by Porter and it was decided to keep her in Norfolk to protect the city and harass the Fed-erals.

This was not be as McClellans peninsula campaign led to the confederacy to abandon and burn Norfolk. The CSS Virginia was lightened to make her able to get to Richmond, but could not get to the 18 foot draft recommended and now much of her wooden hull was exposed. So, the 300 dispirited crew were put ashore at Craney Island and the ship burned. It blew up at 5 AM waking many locals. John Porter's dream and hard work were gone. However, the Porter-Brooke design would be repeated in over 22 confederate ironclads which were commissioned. They all suffered from the confederation lack of skilled labor and materials. In a sense the South never recovered from the loss of the CSS Virginia, which allowed the North to move up the James, where the Monitor and other ships were repulsed by shore guns manned by the crew of the Virginia, who savored the moment.

After the loss of Norfolk, Porter was assigned to the Richmond Naval Yard and worked on several new ironclads. He was then given overall supervision of all the 22 ironclads the confederacy was able to produce.

After the war he returned to his hometown of Portsmouth and died in 1893.

Full credit for this brief summary goes to to our former neighbor, John Quarstein, who has written and lectured on every aspect of the Civil War. Go hear him whenever you can and don't miss the new Monitor Center.

By Bob Howard

Hampton's Crabs & Terrapins

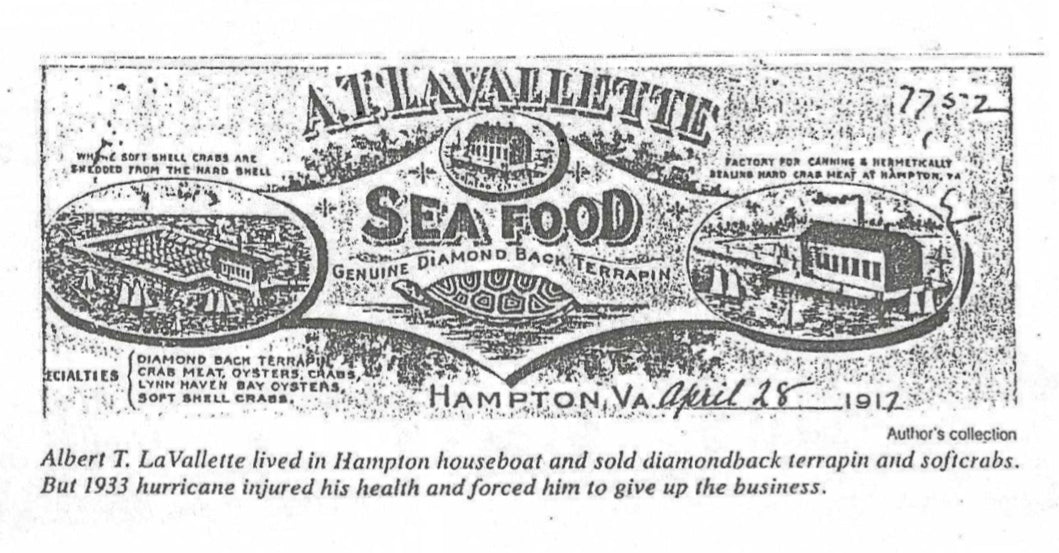

A Frenchman by the name of Albert T. LaVallette, lived on a houseboat on Hampton's waterfront (between LaSalle and Merrimac Shores near Church-Creek) for several decades until 1933, and raised diamondback terrapins. People in those days loved to eat terrapin stew. Every Saturday he would ship terrapins, crabs and crab meat to the Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York markets by truck.

His houseboat was built during the late 1800's and was named "Valetta."

The plant is shown on Captain LaVallette's business letterhead of 65 years ago, a copy of which is attached. Advertising "Genuine Diamond Back Terrapin," it also depicts a crabmeat factory and crab-shedding basin, both operated by LaVallette. The plant and basin was destroyed during the Wednesday, August 23d 1933, hurricane. After that, LaVallette was out of business.

Though called, "Captain," LaVallette never rose above the rank of lieutenant when he served in World War I in command of a Hampton Roads pilot boat on patrol off the Virginia Capes. After the war, he left naval duty to return to his seafood and terrapin business.

What's more, LaVallette's houseboat was furnished with objects of interest from the USS

Constitution, one of the Navy's first men-of-war. For the terrapin farmer was the grandson of a famous father, well-known in Navy history.

The objects and papers from the Constitution had come from LaVallette's grandfather, Captain Elie LaVallette, when he commanded the Constitution from 1825 till about 1828. A navigator's protractor used aboard the Constitution was given to the Mariner's Museum by his grandson's widow in 1947, after she left Hampton to live in New York City.

Albert LaVallette died at Kecoughtan Veterans' Hospital in 1937. When the great hurricane swept the Peninsula in August 1933, 71-year-old LaVallette was injured trying to save his houseboat and his waterfront seafood plant. He lingered four years.

An obituary in the July 14, 1937, Daily Press records the death several days earlier of Hampton's LaVallette. "Captain LaVallette, born in Pennsylvania, owned and conducted a terrapin farm a number of years until it was demolished in the 1933 hurricane," it reads in part. "At the time he received serious injuries."

by Luther L. Alexander, June 26, 1997

Misc. Histories

-

The Little England Chapel

-

Letter from Louise Crone, May 5, 1995

-

Entrance Circle Installation, May 2002

Per resident vote, the City of Hampton installed a traffic circle at the intersection of Eggleston & Catesby Jones in order to slow traffic. The circle was then planted with the help of 13 volunteers from the neighborhood, designed by Gordon Statzer, a certified Master Gardener.

Residents voted to add a brick/granite-faced sign, later designed by resident Teddie Ryan.

One neighbor commented “that’s not a sign... that’s a monument!”